CHRISTOPHER DOYLE

Wong Kar-Wei’s “In the mood for love” shot by his favoured cinematographer, Christopher Doyle, is a fantastic study of the use of artificial light. It is almost entirely shot indoors under artificial lighting, or outdoors at night, still under artificial lighting.

The storyline follows a husband and a wife, who suspect their respective partners of having an affair with each other. Set in 1960s Japan, the film follows the couple as they deal with their heartbreak alone, then together as friends and confidents. However, their feelings develop into something much stronger as they console each other. At no point in the film do they ever act on their feelings, however, their emotional state is the primary factor of the film. A will-they-won’t-they situation. At the very end of the film, the timescales shift, jumping forward to when the two have moved on in their lives, and subsequently all these scenes are shot in natural daylight, as if to shift out from the darkness of their heartbreak.

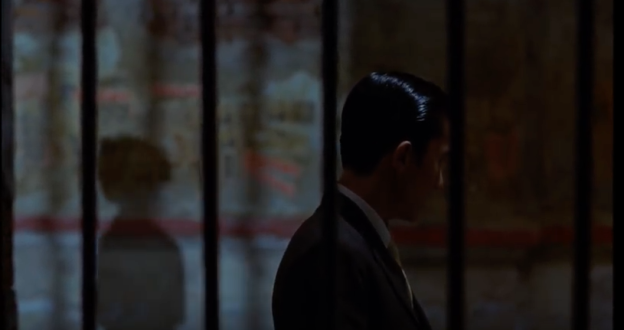

However, for the most part, the film is quite dark, drawing direct correlations not only with the heaviness of their pain, but also the weight of moral judgement of a married man being friends with another man’s wife. The film could be considered quite slow, but the pace gives plenty of time to really engage and connect with the characters. Lighting is used throughout to pick out details and enhance the elements that convey the desired emotion. We often see the character’s faces illuminated with light during conversations, as waves of emotion are highlighted by close shots, using direct lighting, see fig 1. Here the emotion is very raw, so the light is harsh.

Fig 1

The colour tone of the light changes depending on the scene in question. In fig 2, the light is predominantly red, denoting a mix of passion and frustration, and perhaps even suggestive of danger at the potential outcome of their new-found situation.

Fig 2

Light and shade are used to help focus the viewer’s attention. In fig 3 the character Chow Mo-wan is in the foreground, yet the focus is on the shadow cast by Su Li-zhen, as she walks away from him and out of the frame. The lighting has taken on a cold blue hue, to reflect the negative narrative in this scene.

Fig 3

The lack of light works to block out any distracting elements from the scene in fig 4 the main character is a room full of people, yet she is alone, lost in her thoughts. The lighting here is soft and mellow, to reflect her mood.

Fig 4

This film is beautifully shot, not just the lighting, but also the use of slow-motion in parts, the use of framing of the subjects almost entirely throughout the film. There are many lessons to be learned from applying the same rules used in cinematography to still photography.

BRASSAI

Born in Hungary in 1899, Gyula Halasz, later to become known as Brassai, first lived in Paris for a year at the age of three, while his Hungarian father was a professor of French literature at the Sorbonne. He would return to call Paris home, in 1924. Brassai studied painting and fine art in Budapest and Berlin, his love for photography did not develop until he returned to Paris and was working as a journalist. He often walked the city’s streets at night, observing the city under the street lights and the people who come out after dark. It’s rather interesting that his observations came first, to then be documented through photography “I walked around Paris a lot at night and saw many things. I sought a means of expressing these sights that I saw and a woman loaned me a small camera. And so I begun to take night photos in 1930” (ASX, 2011).

Having studied fine art, his photography is of course heavily influenced by this. He approaches his compositions as if creating a painting, thinking about what will be included in the frame, “Photography has nothing to do with painting, but even so there is a frame in which the photograph must be composed.” (ASX, 2011). Brassai believes that all life experiences inform and influence photography. ”I think that it is certain that one doesn’t always photograph with the eyes but with all one’s intelligence.” (ASX, 2011). And of course. Photography is a hugely subjective art form; people will always see an image in different ways, so therefore people will always shoot differently, conveying their own personal approach. Brassai speaks to the need of an understanding of human nature as well as composition, “Photography has one leg in painting and one leg in life but the two things must be combined.” (ASX, 2011). This strikes a chord in me, particularly when I shoot images of friend’s children. I always aim to capture a bit of the child’s personality in the images something that the parents will instantly recognise and value in the keepsake.

Brassai’s ‘Paris by Night’ is a wonderful collection of the images he captured around the city. All shot in black and white, the overarching theme of the cityscape imagery, is the softness of the light. In fig 5, the light almost hand-picks just enough detailing to set the scene. The highlights create shape and form that resemble real life, but not in its entirety. The end result is images that are hugely intriguing.

Fig 5

Looking at his images in the context of light, in figs 5 and 6, Brassai overlays structures and people in silhouette to emphasise the light and give strength to the composition.

Fig 6

Fig 7

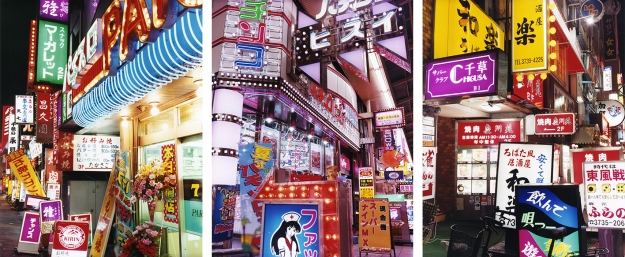

SATO SHINTARO

Sato Shintaro’s collection ’Night Lights’ is shot in the streets of Japan and Osaka, over a two year period. He has purposefully chosen to document the streets as they are seen, day in day out, albeit with one small difference – there are no people. “I have purposefully avoided the more aesthetically pleasing locations such as seaside areas and the well know subcenters in favour of the everyday disorder of the streets” (Night Lights, 1999). The hustle and bustle is still very evident in the individual sign’s struggle for visibility. Each frame is literally flooded with illumination, to the point that it almost all blends into one. That said, there is also a peacefulness contained in these images. There is no motion, no emotion, just the most vivid of artificial colours squeezed into the composition, overlapping and reflecting wherever they can. This series works especially well as multiple images, I fear that one image on its own would greatly lose the impact of the entire set. There is a total of 43 images, and when viewed in sequence, they almost seem to begin to reach a crescendo around image 10 or 11 where the view point is closer so the lights appear to fill the frame better. Conversely around image 31 or 32, the colours begin to darken slightly and move away from the rich vibrant neon yellows and magentas, to include the darker hues of the night sky and the streets.

Figs 8, 9, 10

I find myself lingering over the explosion of colours in fig 8-10 more than the others, which are at the height of the colour explosion within the series.

I greatly admire the quality of this type of light, it is rich yet soft as it is diffused by the very graphics it is there to illuminate. This is quite a compelling concept, and very well executed.

References:

La Mazmorra Cinéfila 2. (2000). In The Mood For Love. [Online Video]. 21 November 2016. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JxUqmjdqVzk&t=21s. [Accessed: 28 October 2017].

ASX. 2011. Tony Ray-Jones Interviews Brassai” Pt. I (1970). [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.americansuburbx.com/2011/08/interview-brassai-with-tony-ray-jones.html. [Accessed 28 October 2017].

ASX. 2011. Tony Ray-Jones Interviews Brassai” Pt. I (1970). [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.americansuburbx.com/2011/08/interview-brassai-with-tony-ray-jones.html. [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Sato Shintaro. 2017. Night Lights. [ONLINE] Available at: http://sato-shintaro.com/work/night_lights/index.html. [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Image References:

Fig 1-4: Screengrabs from La Mazmorra Cinéfila 2. (2000). In The Mood For Love. [Online Video]. 21 November 2016. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JxUqmjdqVzk&t=21s. [Accessed: 28 October 2017].

Fig 5: Brassai, (2017), Untitled [ONLINE]. Available at: http://www.atgetphotography.com/The-Photographers/BRASSAI.html [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Fig 6: ‘Avenue de L’Observatoire‘, Brassai, 1968. Brassai. Brassaï With an introductory essay by Lawrence Durell, [Online]. -, 20, 21. Available at: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2614_300299016.pdf [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Fig 7: ‘Nuit de Longchamps’, Brassai, 1968. Brassai. Brassaï With an introductory essay by Lawrence Durell, [Online]. -, 20, 21. Available at: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2614_300299016.pdf [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Fig 8: Sato Shintaro, (1997-99), 19 Night Lights [ONLINE]. Available at: http://sato-shintaro.com/work/night_lights/index.html [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Fig 9: Sato Shintaro, (1997-99), 20 Night Lights [ONLINE]. Available at: http://sato-shintaro.com/work/night_lights/index.html [Accessed 28 October 2017].

Fig 10: Sato Shintaro, (1997-99), 21 Night Lights [ONLINE]. Available at: http://sato-shintaro.com/work/night_lights/index.html [Accessed 28 October 2017].